August

Hello!

August is a month for DuBois. I first read him, via The Souls of Black Folk, in August 2002, as assigned summer reading for my junior year AP English class, alongside The Autobiography of Malcolm X, 1984, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. My mind was pleasurably blown by all four books, which I did dutifully read, because I was the sort of kid, teenager, who read all of my summer reading, every summer, sometimes early, with few notable exceptions. Exception: my dad had, and still has, a habit of listening to certain audiobooks on repeat, and I mean on repeat, and the summer between sixth and seventh grades, or seventh and eighth grades, Journey to the Center of the Earth was one of those books. Having heard the word so many times before seeing the word, that Reykjavik is spelled Reykjavik also pleasurably blows my mind. I thus overheard many passages—especially tuned into those about meeting prehistoric fish and dinosaurs and people far beneath the earth's crust—about a million times while my dad cooked dinner or cleaned the kitchen or did his own reading, and I wrote my summer reading report on that required book based on those second-hand listenings. I still feel some twinge of guilt because I can hear myself protesting to my seventh-or-eighth grade English teacher that look, you couldn't tell the difference, could you? (I also wrote a report on The Odyssey based exclusively on having watched the Wishbone adaptation, also a million times, an arguably worse dissemblance about which I for some reason never felt any guilt.)

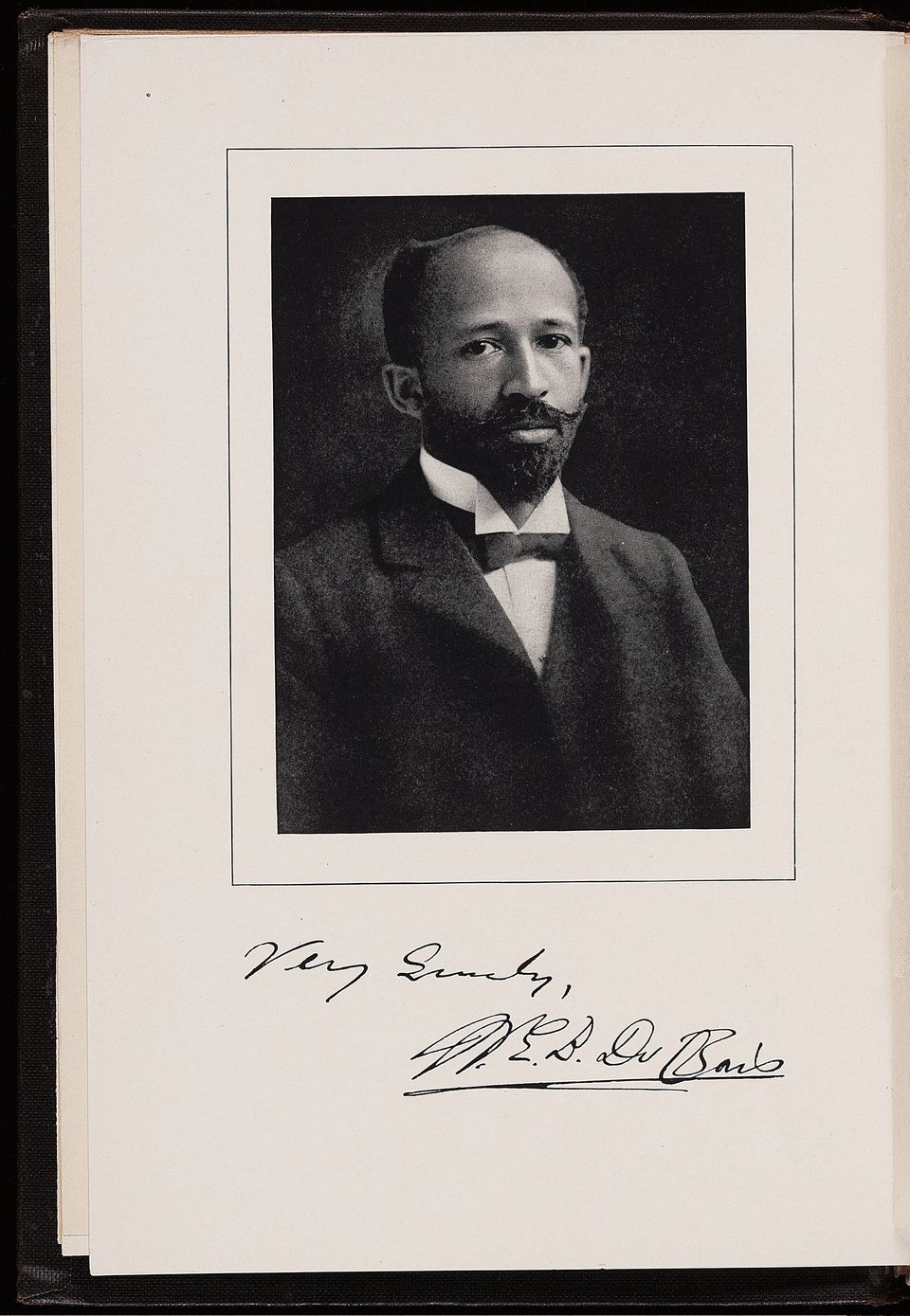

Anyways, August was a month of rediscovering and re-evaluating DuBois, via his landmark sociological work, The Philadelphia Negro (1899) and his speculative fiction, including short stories "The Comet" (1920) and "The Princess Steel" (c. 1908-10), collection of prose and poetry, Darkwater (1920), and novel Dark Princess (1928).

A warning: this is a side-winding one.

Before we begin, I'd like to call attention to my favorite read of DuBois, by Saidiya Hartman in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, in which Hartman imagines the young sociologist conducting his surveys, aghast at the immoral looseness of love he observes, because DuBois does not always do women, or men, and their consensual adult choices about sex and love, right in his writing, and it's thus only fair to share Hartman's imagining of DuBois:

Illicit sex had introduced DuBois to lovemaking and nearly undone him.

He never lived down the guilt, which had accompanied the pleasure of losing his virginity in an act of adultery with an unhappy wife. When he arrived in the hills of Tennessee as a lonely young teacher, he was so ignorant about sex that he lacked even the basic knowledge of the anatomical difference between men and women. None of his peers believed that anyone could be so innocent and stupid, until they realized he was telling the truth.

With this is out of the way (or properly in the way), I'd like to talk for awhile about DuBois, who has been talked about a lot already (not by me), so I hope you'll forgive me for adding, probably needlessly, to the conversation. Mostly, I feel a kinship to him in that probably inappropriate way in which he feel kinship with people we've never been in the same room with, and thus don't really know. But also, I feel a tension with him, also in that inappropriate way. Which is all to say, that I feel a kinship and tension with myself, those parts of me which DuBois makes a convenient corkboard on which to pin them.

He was born and raised in Great Barrington, Massachusetts on the fringes of upper-class society, educated at all-Black Fisk University in Nashville before transferring to Harvard for a second BA and a PhD. He graduated from Harvard and couldn't get a job (no huge surprise there for us, but unpleasant surprise to him). A couple years later, he was invited to the University of Pennsylvania to conduct a city-wide survey of black people living in Philly, to find out, as they didn't-quite-put-it, what the goddamn hell is wrong with all these black folks?

DuBois did conduct the surveys, and published his results in The Philadelphia Negro, making his mark on the way that so-called ethnographic studies are performed to this day. He was earnestly opposed to the outside-in, deductive sociological methods to understanding human nature that was in vogue at the turn of the twentieth century—come up with a universal law, apply to it to people—because, turns out, most of those laws were emerging from a euro-centric and white supremacist unconscious (at best). What UPenn really wanted DuBois to "discover" was a universal law that could help white folks understand why there was so much crime, poverty, waywardness, and misery in the black slums of Philly. Instead, DuBois concludes that a systemic application of exclusionary and racist laws and policies acted as barriers to education, jobs, and stable housing. The result of which were people doing their best to get by (he doesn't quite put it this way; Hartman does), living in poverty, chasing jobs (and men, and women), a general atmosphere of suffering and misery. In his later autobiography, he writes, about his time in Philadelphia

The world was thinking wrong about the race, because it did not know. The ultimate evil was stupidity. The cure for it was knowledge based on scientific investigation....The fact was that the city of Philadelphia at that time had a theory; and that theory was that this great, rich, and famous municipality was going to the dogs because of the crime and venality of its Negro citizens, who lived largely centered in the slum at the lower end of the seventh ward....Of this theory back of the plan, I neither knew nor cared. I saw only here a chance to study an historical group of black folk and to show exactly what their place was in the community.

(Later, but not really, about this same passage still holding true about so many cities, so many leaders. Time! The greatest dissembler of them all.)

At the same time, The Philadelphia Negro reveals a man surely torn about his own race. He segments black people into categories; roughly, good, better, bad, worse. He just doesn't quite get how he can be black and they can be black and people can see them as the same, while he feels himself to be so utterly different from the kind of folk he meets in the slums. But at the same same time, he knows there's something wrong with how everybody, up to and including himself, are thinking about blackness, about humans, about knowing.

A decade later, he writes "The Princess Steel," which imagines an instrument called a megascope that allows people to view the Great Near, that is, those giant forces shaping life that are too close to us to see. In 1920, he publishes the short story, "The Comet" (anthologized in Dark Matter, of which I have spoken), about a comet that hits New York and seems to have left only two people—a black man and a white woman—alive in its wake. There is a scene in which the two observe from the top of the Metropolitan Tower the empty city beneath,

He watched the city. She watched him. He seemed very human—very near now.

"Have you had to work hard?" she asked softly.

"Always," he said.

"I have always been idle," she said. "I was rich."

"I was poor," he almost echoed.

"The rich and the poor are met together," she began, and he finished: "The Lord is the Maker of them all."

"Yes," she said slowly, "and how foolish our human distinctions seem—now," looking down to the great dead city stretched below, swimming in unlighted shadows.

"Yes—I was not—human yesterday," he said.

She looked at him. "And your people were not my people," she said; "but today—" She paused. ...

"Death, the leveler!" he muttered.

DuBois's fiction has been called, and I won't disagree, melodrama. Dark Princess, his second novel, generously applies romantic trope upon trope as he imagines a romance between an Indian princess, Kautilaya of Bwodpur, and a black man, Matthew Townes. Through the course of the novel, they are united in their struggle for the liberation of all people of color throughout the world, and ultimately birth a child together.

The stories are utopian in the sense that they imagine—not always through wonderful events or revelatory inventions like the megascope; in the case of "The Comet," through "Death, the leveler!"—a world in which the conditions of black people are radically changed such that we feel ourselves to be loved, lovable, human; and in which DuBois sees them as loved, lovable and human. They are stories that are, still, I think, arguing against that "great theory" about black people that DuBois knows is lodged into the minds of white people everywhere. The theory being, fundamentally, that we are not human.

The stories are, in their lush prose and unabashed earnestness, quests for connection, quests for pleasure, maybe even for DuBois himself, writing a world in which he can feel a less complicated, less ambivalent pleasure. They reveal slight glimpses of what might be, before, often, that glimpse is snatched roughly away. In the story "The Princess of the Hinter Isles," collected in Darkwater, DuBois writes of a lonely princess who has glimpsed "the mighty Empire of the Sun," where she longs to rest, and from which she is separated by a vast chasm,

Then up from the soul of the princess welled a cry of dark despair,—such a cry as only babe-raped mothers know and murdered loves. Poised on the crumbling edge of that great nothingness the princess hung, hungering with her eyes and straining her fainting ears agains the awful splendor of the sky.

Out from the slime and shadows groped the king, thundering: "Back—don't be a fool!"

But down through the thin ether thrilled the still and throbbing warmth of heaven's sun, whispering "Leap!"

And the princess leapt.

DuBois's journey to the center of Philadelphia was a leap into the dark, and a leap across to "the mighty Empire of the Sun," what Empire might have looked and sounded and smelled different to DuBois at different phases of his life. Maybe sometimes the sturdy halls of Harvard. Other times, the empty, Death-leveled streets of New York, where he could be only exactly who he felt himself to be, and not how other people—black and white—saw him to be.

DuBois always knew who was watching him and calling him foolish. He thought other people—including other black people—foolish in turn, and incompletely understood their turns to pleasure, to romance in the face of harsh life. But he made moves over the course of the rest of his life to find his own kind of pleasure, his own kind of understanding and romance. Maybe he turned to science fiction as a realm in which to explore ideas that otherwise may have been dismissed as innocent, stupid, romantic in the "harder" realm of social science. He wrote some melodramatic ass romantic ass stories about princesses and comets and this brings me so much pleasure, like peeling back a mask (okay okay, a veil) and seeing a friend.

Part of what I loved about writing reports based on wayward readings of texts—half-listened to audiobooks, a PBS kids' show—was the feeling that I, a very rule-abiding student, was getting away with something. I was leaping over their heads, I was winking behind their backs, I was revealing slantwise the parts of me that I could not trust them to see head-on. I am and ever have been caught in the same little power struggles DuBois might have felt he was trapped in, and pushing against the same great theory. And I could leap, and I could wink, and I could try to write my way to the center of myself, myself, my own human self.

This is all a long way of saying, I'm so pleased by DuBois's journeys to science-fiction. I am so pleased for the pleasure, for the freedom, he might have found there. I don't know if I would like him very much, were I to meet him in a room. I know I like his writing, which is also a version of him. And that, too, brings me pleasure. The different people we are, the different ways in which we can know parts of each other—dissembling, tricking, avoiding, revealing.

Until next time,

Endria

Member discussion