March

Hello!

I am going to cut right to the quick: March was for Gayl Jones. This will be a Gayl Jones note. And what better month for Gayl Jones than March, which marks the season just before the season of renewal. March is the season of lying wet and still, covered by mud, quietly biding one's time before spring's noisy emergence. A season of diminished patience and renewed expectation and an entire lost hour. I declare March to be Gayl Jones Season. Here are the Gayl Joneses of March:

Corregidora

“My great-grandmama told my grandma the part she lived through that my grandma didn't live through and my grandma told my mama what they both didn't live through and my mama told me.”

I read Corregidora, Jones's debut novel about how trauma lasts, how enslavement and sexual violence and the need to tell our story lasts through generations of women (as Darieck Scott has said, "talking about epigenetics before epigenetics were a thing!") in college. I was 21 or 22, just a handful of years younger than Jones was when she wrote the book. If I had realized it at the time, I would have lost my mind with jealously and, perhaps, not been able to recognize its greatness for pure blind envy. No, I read it the way I read most books in my 20s, taking for granted that the work and the worker was untouchable, existing in a sphere apart from me, held away by some uncrossable border—time or age or generation or race or gender.

“This girl had changed the terms, the definitions of the whole enterprise. So deeply impressed was I that I hadn’t time to be offended by the fact that she was 24 and had no right to know so much so well. She had written a story that thought the unthinkable: that talked about the female requirement to make generations as an active, even violent political act.” — Toni Morrison, Jones's first editor at Random House

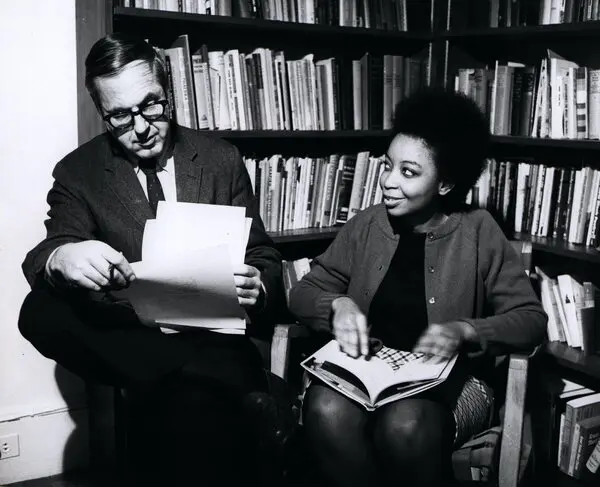

I re-read Corregidora this month knowing full well how young Gayl Jones was when she wrote it, knowing also that there is no uncrossable border between writer and reader, knowing that Jones knew that too (though she has perhaps been successful in holding a boundary). No, Jones was a young black woman doing something so new and boundary-breaking and scary and disturbing that, I think, she could only have been discovered by another black woman genius, Toni Morrison. And I think about that, the way I think about Alice Walker and Zora Neale Hurston, and Claudia Tate and 12 Black Women Writers. I think about the women who have reached for and held out and brought forward the work of minds that are just beyond where the rest of us are, refusing to allow intimidation or offense become barriers to new ways of thinking and knowing.

Ursa, Corregidora's narrator, finds herself unable to make meaning of trauma in the way her mother and her grandmother and her great-grandmother have taught her is the only way to make meaning. And this is, in part, what Corregidora is: a finding-of-one's-way to a new kind of making (and being unable to make) meaning, make life.

Eva's Man

“How did it feel?” Elvira asked.

“How did you feel?” the psychiatrist asked.

“How did it feel?” Elvira asked.

“How do it feel, Mizz Canada?” the man asked my mama. She slammed the telephone down.

“Eva. Eva. Eva,” Davis said.

“My hair looks like snakes, doesn’t it?” I asked.

Eva's Man was Jones's second novel. The narrator, Eva, is in prison for murdering and mutilating her lover. Eva's narration of this event, of her childhood, of violent and sexual acts with men and women are a litany of intrusions unto Eva. She is a woman onto whom evil has been projected, again and again. Her story changes and trembles and questions itself; it withholds linearity, certainty, a story, a reason. Ultimately, the story refuses the reader access to what everyone wants from Eva: her feelings, her inner self.

Palmares

In Claudia Tate's 1979 interview with Gayl Jones in Black Women Writers at Work, Jones says that she has just finished writing her third novel, Palmares.

It was finally published in 2021, after a 22 year hiatus. I'll write more about this one when I finish (I'm halfway through its 500 pages), but for now, I am interested in the ways that Jones shows us the world, history, generations through the eyes of Almeyda, the narrator. We meet Almeyda as a 7 year old black girl enslaved in Brazil in the 17th century. We follow her to her "freedom" in Palmares (the famed Brazilian quilombo governed by King Zumbi) and her marriage to the warrior Anninho. Almeyda is in some ways as inscrutable as Eva; she does not always share what she feels or knows, what she thinks of all that she sees. And yet is only through what she sees that we come to know the world she inhabits. The world as she knows and tries to discern it. What do we know when we see the world through Almeyda, the enslaved, the woman, the haunted?

I find myself thinking again of Jones's own quietness. And of the quietness of Ursa, Eva, Almeyda. I think of Toni Cade Bambara talking about one of her short stories:

"I brought Virginia out...the sister in "The Organizer's Wife," because I wanted to know what those quiet-type sisters sound like on the inside.

And boy, don't the whole world want to know what these black women are like on the inside? As a quiet-type girl myself, I think about times in which quietness was the only choice I could make: to hold apart from everyone out there what I sounded like on the inside. That was my realm, my power.

I can't help but read Jones's quiet women as supremely autonomous and queerly assertive. And oh, there is so much queerness in Gayl Jones. Problematic queerness yes, but queer queerness. This is how I read Jones's women: deep buried, refusing to come out not because there is nothing to reveal, but because the conditions are not right for revelation; the crossing would be too treacherous.

So, make thyself resplendent with mud; prostrate thyself in wait; renew thy patience; be quiet. The time for emergence will come!

Until next month,

Endria

Member discussion